Revue de presse

Gazette ULM – Juin 2024

Baroudage.com

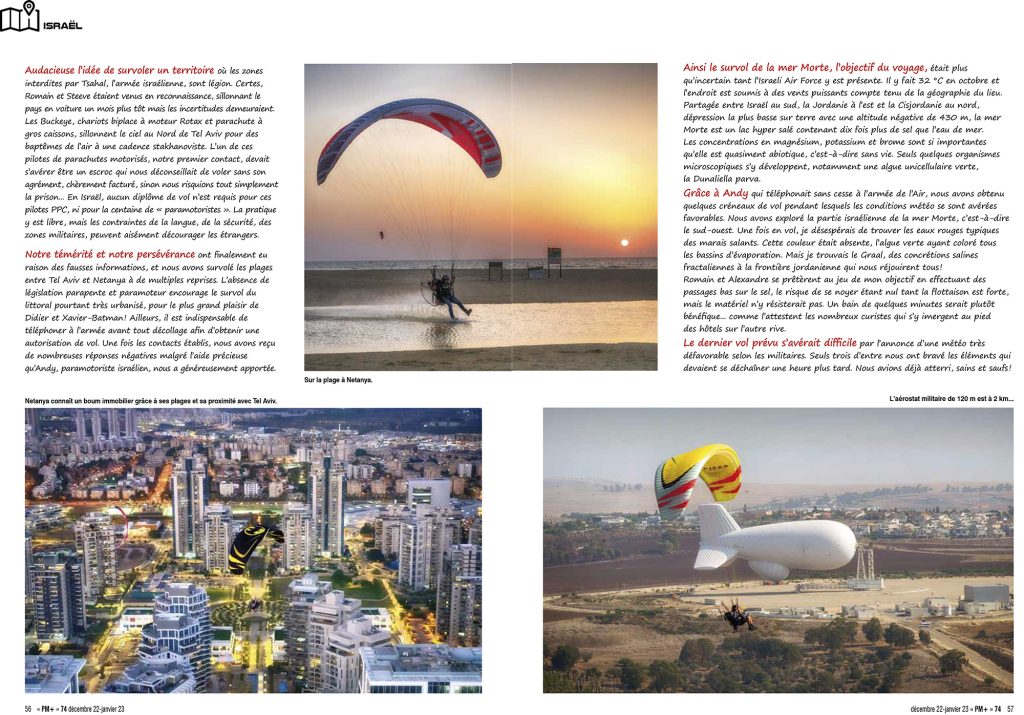

Magazine PARAMOTEUR – Décembre 2022

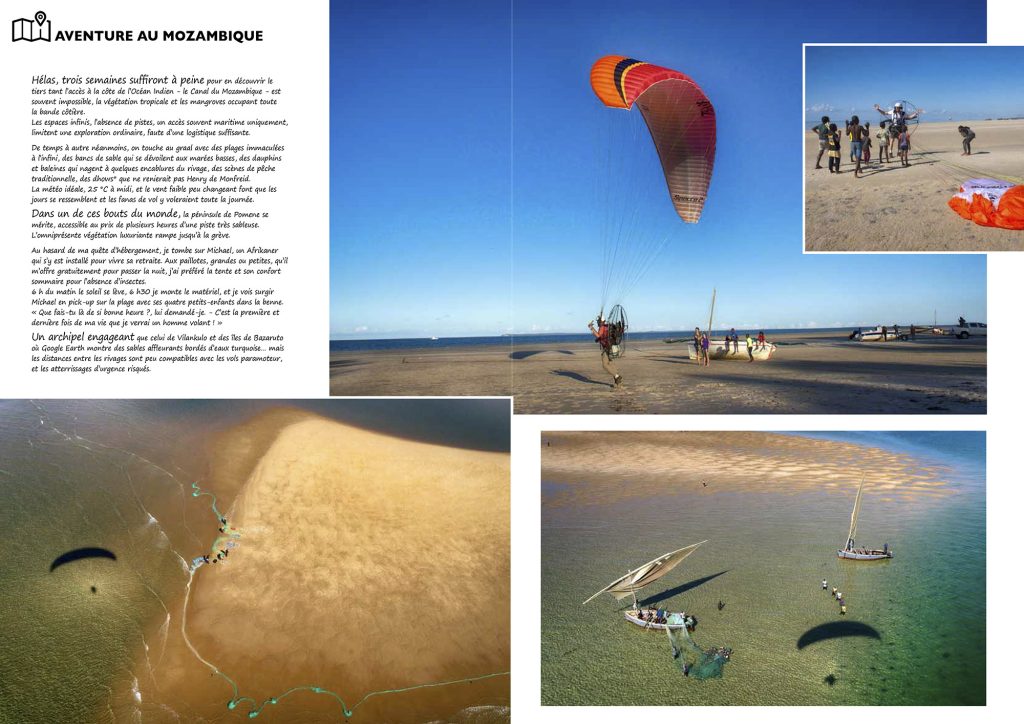

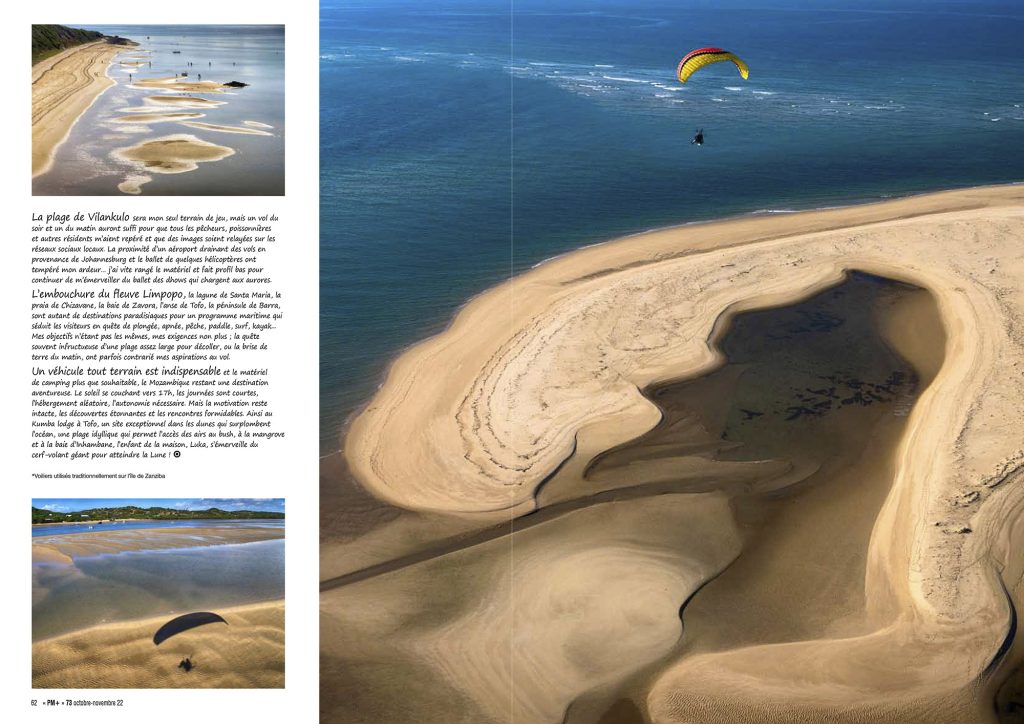

Magazine PARAMOTEUR – Octobre 2022

Shades of Color

Lire le texte de l’article

How and when did you start photography, and what was your learning path?

I was not 20 years old when I left with a camera in Egypt, hitchhiking. I climbed the pyramid of Cheops today. Of course, wanting to climb it sends you directly to prison,but I had the opportunity in 2019 to fly over it in a paramotor, an incredible chance for a photographer. But it was a few years later, in Morocco, where I lived for 2 years, the desert approach, and especially the fascination of the sands imprinted in me forever.

What are your main influences?

During my military service in cooperation in Casablanca, I met some talented photographers who strongly influenced my style. The light, the framing, and the harmony of forms and colors are my tools. Landscape and reportage are my playgrounds.

In the ’90s, when I returned to France. I won many distinctions, notably the Grand Prix d’Auteur of the French Federation of Photography and the first prize of the ‘Ballantine Finest Intemational Photography Award. ‘In those years, I published a few books on the southwest of Paris.

What is the part of photography in your life, and has it changed your vision of the world?

I am a physicist by profession and an exploratory photographer by passion. I have pursued a quest for deserts and dunes, traveling in photographic and anthropological research on all continents. I discovered the geomorphology of the sands, the color, the vegetation, and the man in the desert.

Tam the author of 3 books on the world’s deserts. First, ‘Dunes’ in 2002, whose French, English, and German versions were published in partnership with Geo and National Geographic, then ‘Rouge Desert’ in 2005, and ‘Oasis’ in 2018. The quest for deserts has no end. I continue the adventure of the sands through photography and travel.

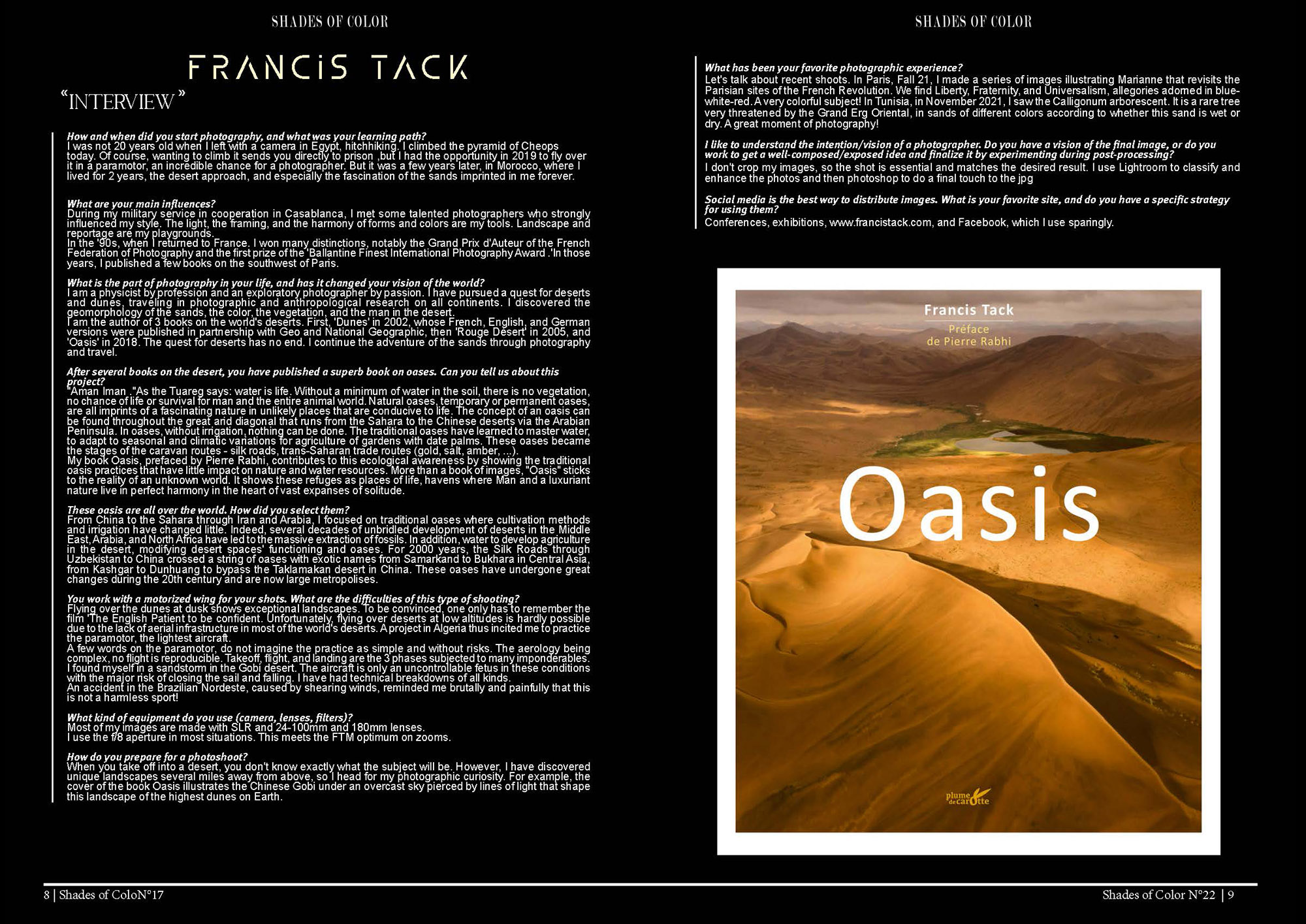

After several books on the desert, you have published a superb book on oases. Can you tell us about this project?

« Aman Iman « As the Tuareg says: water is life. Without a minimum of water in the soil, there is no vegetation, no chance of life or survival for man and the entire animal world. Natural oases, temporary or permanent oases, are all imprints of a fascinating nature in unlikely places that are conducive to life. The concept of an oasis can be found throughout the great arid diagonal that runs from the Sahara to the Chinese deserts via the Arabian Peninsula. In oases, without irrigation, nothing can be done. The traditional oases have learned to master water, to adapt to seasonal and climatic variations for agriculture of gardens with date palms. These oases became the stages of the caravan routes – silk roads, trans-Saharan trade routes (gold, salt, amber, …).

My book Oasis, prefaced by Pierre Rabhi, contributes to this ecological awareness by showing the traditional oasis practices that have little impact on nature and water resources. More than a book of images, « Oasis » sticks to the reality of an unknown world. It shows these refuges as places of life, havens where Man and a luxuriant nature live in perfect harmony in the heart of vast expanses of solitude.

These oasis are all over the world. How did you select them?

From China to the Sahara through Iran and Arabia, I focused on traditional oases where cultivation methods and irrigation have changed little. Indeed, several decades of unbridled development of deserts in the Middle East, Arabia, and North Africa have led to the massive extraction of fossils. In addition, water to develop agriculture in the desert, modifying desert spaces’ functioning and oases. For 2000 years, the Silk Roads through Uzbekistan to China crossed a string of oases with exotic names from Samarkand to Bukhara in Central Asia, from Kashgar to Dunhuang to bypass the Taklamakan desert in China. These oases have undergone great changes during the 20th century and are now large metropolises.

You work with a motorized wing for your shots. What are the difficulties of this type of shooting?

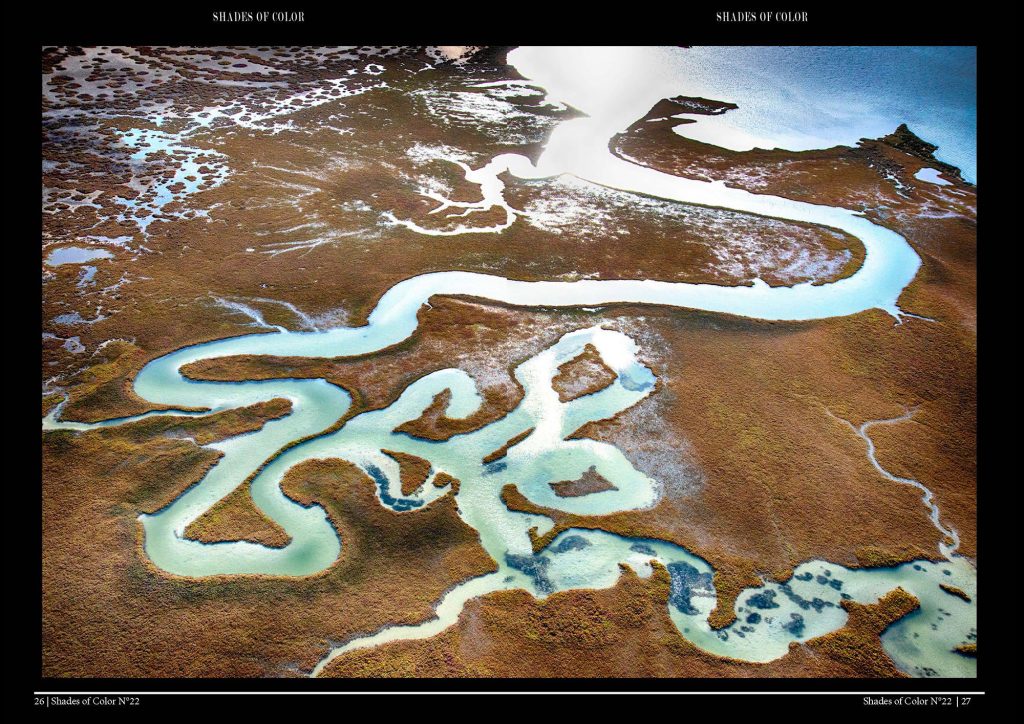

Flying over the dunes at dusk shows exceptional landscapes. To be convinced, one only has to remember the film ‘The English Patient to be confident. Unfortunately, flying over deserts at low altitudes is hardly possible due to the lack of aerial infrastructure in most of the world’s deserts. A project in Algeria thus incited me to practice the paramotor, the lightest aircraft.

A few words on the paramotor, do not imagine the practice as simple and without risks. The aerology being complex, no flight is reproducible. Takeoff, flight, and landing are the 3 phases subjected to many imponderables. I found myself in a sandstorm in the Gobi desert. The aircraft is only an uncontrollable fetus in these conditions with the major risk of closing the sail and falling. I have had technical breakdowns of all kinds.

An accident in the Brazilian Nordeste, caused by shearing winds, reminded me brutally and painfully that this is not a harmless sport!

What kind of equipment do you use (camera, lenses, filters)?

Most of my images are made with SLR and 24-100mm and 180mm lenses.

I use the f/8 aperture in most situations. This meets the FTM optimum on zooms.

How do you prepare for a photoshoot?

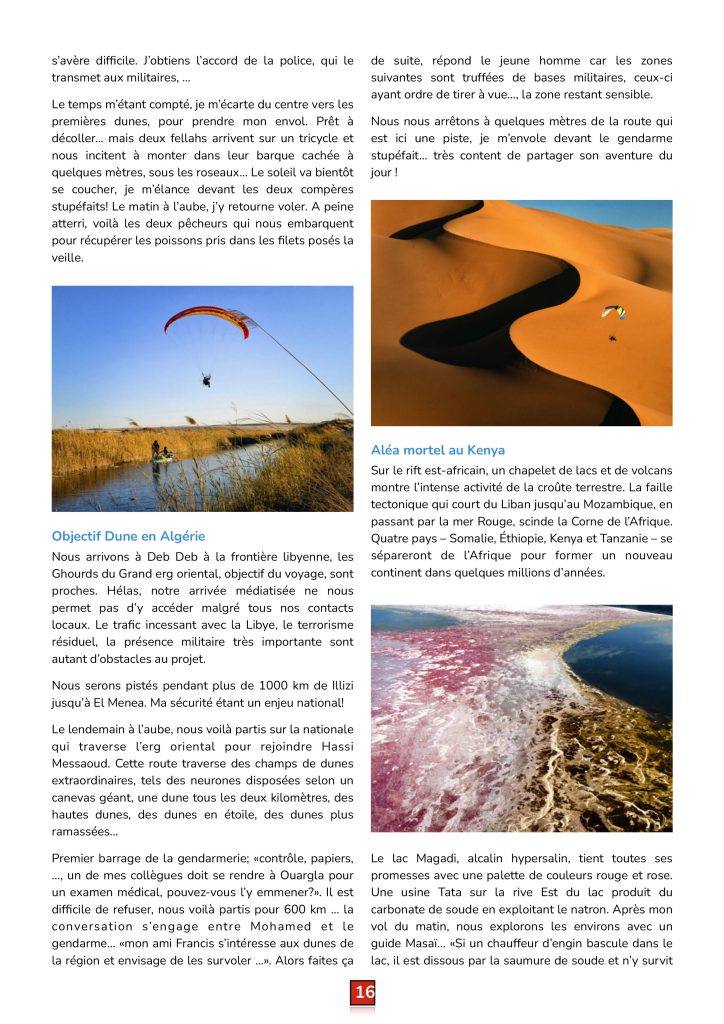

When you take off into a desert, you don’t know exactly what the subject will be. However, I have discovered unique landscapes several miles away from above, so 1 head for my photographic curiosity. For example, the cover of the book Oasis illustrates the Chinese Gobi under an overcast sky pierced by lines of light that shape this landscape of the highest dunes on Earth.

What has been your favorite photographic experience?

Let’s talk about recent shoots. In Paris, Fall 21, I made a series of images illustrating Marianne that revisits the Parisian sites of the French Revolution. We find Liberty, Fraternity, and Universalism, allegories adomed in blue- white-red. A very colorful subject! In Tunisia, in November 2021, I saw the Calligonum arborescent. It is a rare tree very threatened by the Grand Erg Oriental, in sands of different colors according to whether this sand is wet or dry. A great moment of photography!

I like to understand the intention/vision of a photographer.

Do you have a vision of the final image, or do you work to get a well-composed/exposed idea and finalize it by experimenting during post-processing?

I don’t crop my images, so the shot is essential and matches the desired result. I use Lightroom to classify and enhance the photos and then photoshop to do a final touch to the jpg.

Social media is the best way to distribute images. What is your favorite site, and do you have a specific strategy for using them?

Conferences, exhibitions, www.francistack.com, and Facebook, which I use sparingly.

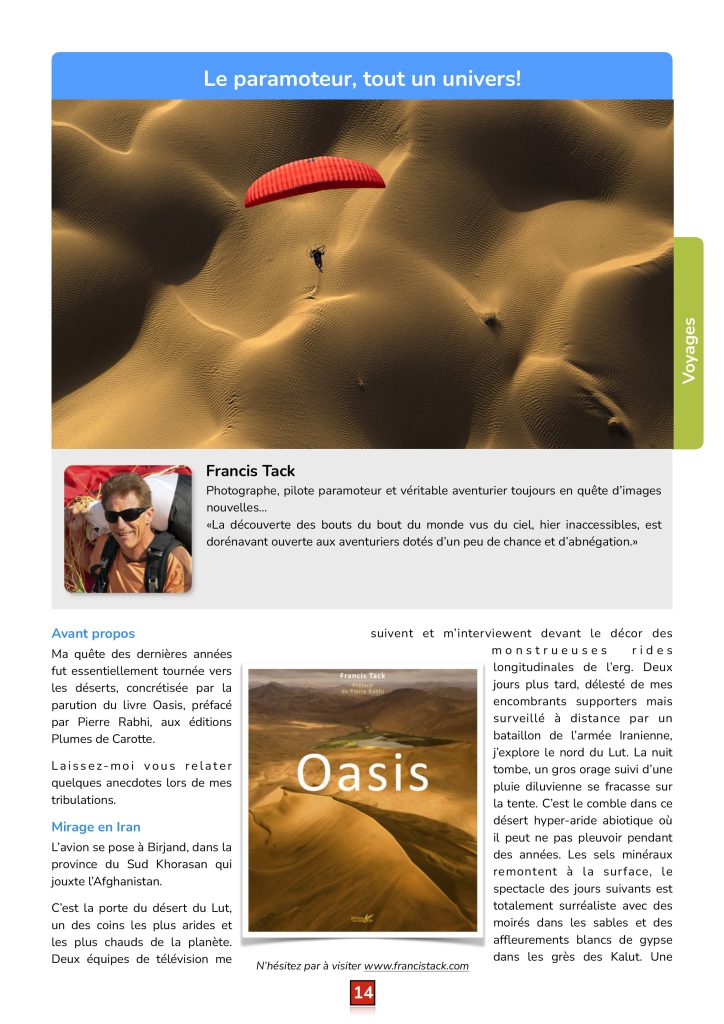

Francis Tack

Préface de Pierre Rabhi

Oasis

plume

de Carotte

8 | Shades of ColoN°17

Shades of Color N°22 | 9

Digitalna Kamera

Magazine PARAMOTEUR – Avril-Mai 2016

Texte et photos: Franck Simonnet

Depuis de nombreuses années. Francis Tack poursuit sa quête de déserts et de dunes, parcourant les continents pour y découvrir de nouveaux paysages et d’autres visages. Ces travaux furent réunis dans deux ouvrages, Dunes et Rouge Désert, publiés en 2002 et 2005. Les sables sont une source d’inspiration inépuisable pour le photographe qu’il est.

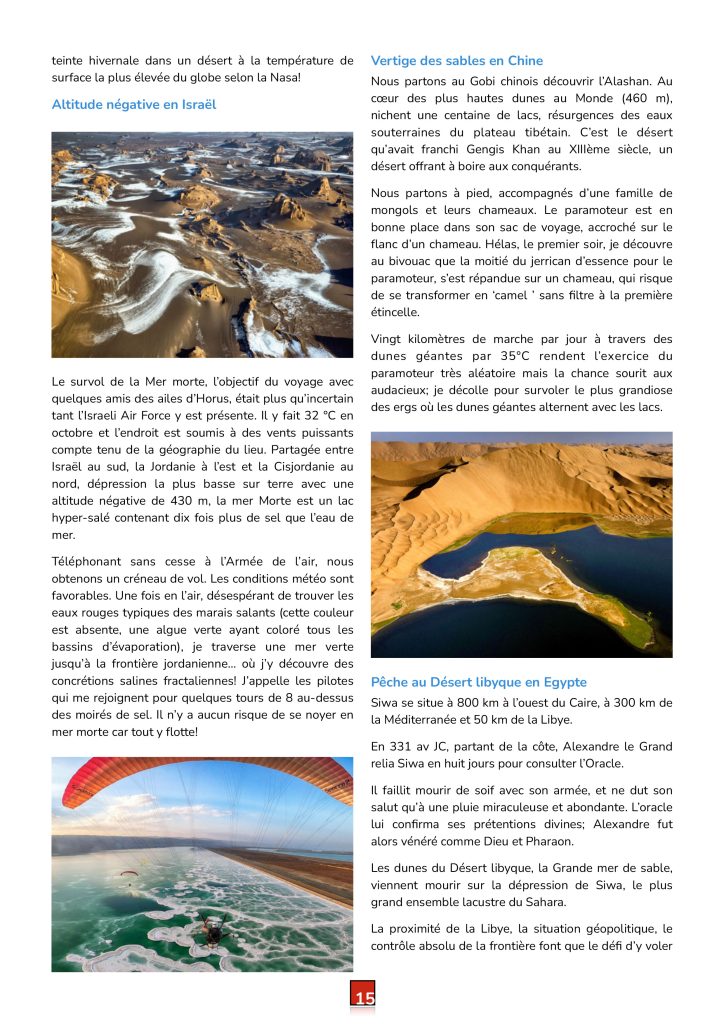

Hélas, le survol des déserts à basse altitude n’est guère possible faute d’infrastructures aériennes dans la plupart des déserts du monde. C’est pour cette raison qu’il s’est intéressé au paramoteur dont il est breveté depuis 2008. Mais avant de partir en vadrouille avec son engin volant, il a fallu que l’idée fasse son chemin, Malgré son désir d’évasion, la technicité de la pratique l’a freiné dans son élan. Il lui fallait être suffisamment à l’aise en l’air avant de penser à autre chose, devenir pilote avant d’être photographe volant. Le déclic s’est produit lors d’un premier voyage en Tunisie. La beauté de ses clichés rendus possibles par la perspective aérienne l’a convaincu de la pertinence de son choix. Depuis lors, rien ne semble arrêter le chasseur de dunes.

Vous ne serez pas surpris d’apprendre que j’ai croisé pour la première fois Francis à la bordure tunisienne du Grand Erg Oriental. Sa grande silhouette et son envergure d’albatros sont inimitables. Affable et charismatique, ses qualités d’orateur n’ont pas leur pareil. Lorsqu’il conte ses innombrables tribulations, l’auditoire est captivé.

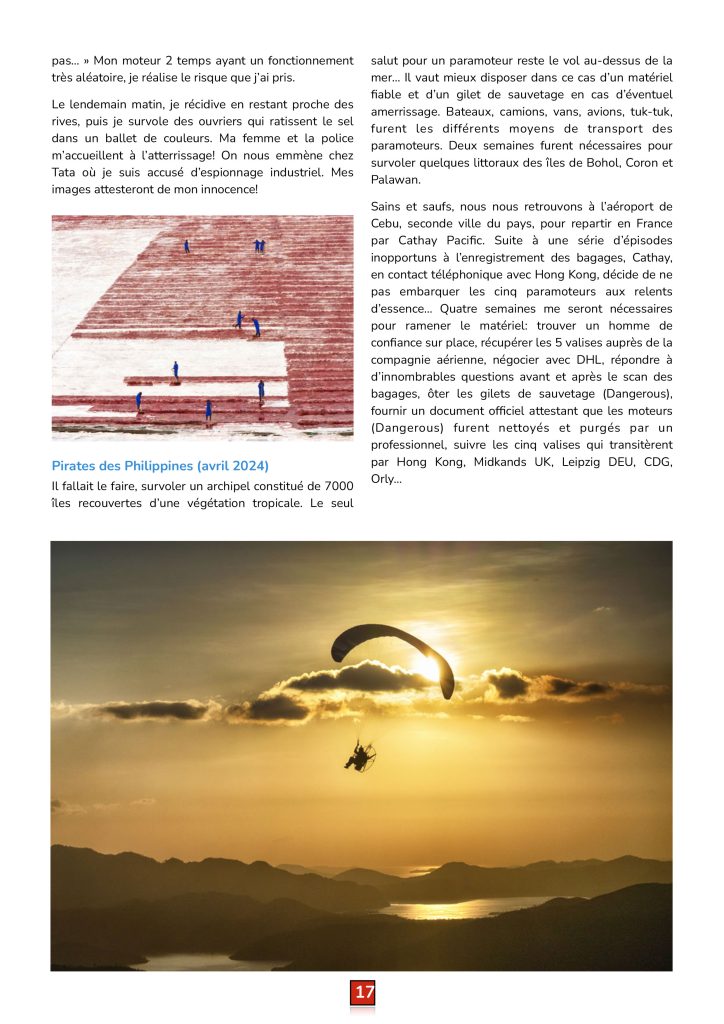

Il lui est arrivé des pannes techniques de toutes natures avec pour conséquence : un amerrissage de survie au milieu d’une rivière au Maroc, une panne moteur au-dessus des parcs à huitres à Marennes, un atterrissage forcé dans la boucle d’un canyon à Madagascar, suivi de quatre heures de marche en espace aride pour retrouver la civilisation… Et il y a bien d’autres péripéties qu’il distillera tout au long du séjour.

Quelques-unes sont plus marquantes comme s’être empêtré dans des fils électriques au Vietnam. De retour en métropole, ce spécialiste d’optiques et de lasers dans le civil, n’a pas hésité à subir une intervention de chirurgie rétractive au laser comme le font les soldats américains, Il a ainsi gagné quelques dixièmes et amélioré son acuité visuelle.

Sa convoitise des dunes l’a guidé au Brésil où, au Nordeste, se trouve un ensemble dunaire unique situé à l’équateur. Qui plus est, l’été, la pluie baigne les dunes. Mais c’est aussi la période des alizés. Avec le vent soufflant en journée à 40 km/h, la pratique du paramoteur est devenue plus qu’aléatoire et un incident grave en fin de parcours lui a rappelé que ce n’était pas un sport anodin! Cet épisode n’a pas remis en cause son envie de voler, et quand il évoque le paramoteur, il parle bien d’un sport physique et technique. Il court donc régulièrement pour rester en bonne forme, et quand il n’est pas en voyage, il s’entraîne à décoller et atterrir même s’il n’est pas un adepte des tours de piste. Son dernier séjour en Tunisie, à côtoyer des pilotes dont l’intérêt n’était pas que la photographie, lui a montré une autre facette du paramoteur. Rejoindra-t-il ceux qui aiment les vols de distance, les stakhanovistes du paramoteur comme il les nomme? Avant de repartir sous d’autres cieux photographier les grains de silice qui t’obnubilent, il partage avec nous sa dernière anecdote ;

« Nous franchissons plusieurs barrages militaires successifs où le coffre du véhicule est systématiquement ouvert. La côte méditerranéenne n’est plus très loin. À un énième contrôle, les sacs sont fouillés et le soldat en sort une bouteille… de Pastis qu’il montre triomphalement à ses deux collègues comme s’il avait trouvé l’objet compromettant. Avant qu’ils ne la boivent, car celle-ci est au trois-quarts pleine, je sors calmement de la voiture.

– Comment? De l’alcool? Mais non les gars, vous n’y êtes pas du tout. C’est un additif à l’essence, Vous voyez le bidon là, vous voyez le moteur du paramoteur. À raison de quelques pour cent, c’est indispensable pour que la machine fonctionne! Eh oui, débrouillez-vous avec la police qui m’a donné son accord… Ce n’est pas du Whisky les gars, sinon il n’y en aurait plus ! Pourquoi reviendrais-je avec une bouteille pleine? De toute manière, c’est ha-ram (interdit), non?

Notez qu’entre l’arabe et l’anglais, nous n’avons pas trois mots en commun pour communiquer. Je les laisse perplexes et remonte dans la voiture. Je les vois refermer les sacs et y replacer la bouteille. Quelque dix heures plus tard, nous buvons un apéritif bien mérité. En conclusion, paramoteur ou pastaga, il faut choisir !»

Si aujourd’hui Francis sait voler, sa quête n’a pas de fin et il continue l’aventure des sables sur son tapis volant.